Team:Berkeley/Human Practices

From 2010.igem.org

- Home

- Project

- Parts

- Self-Lysis

- Vesicle-Buster

- Payload

- [http://partsregistry.org/cgi/partsdb/pgroup.cgi?pgroup=iGEM2010&group=Berkeley Parts Submitted]

- Results

- Judging

- Clotho

- Human Practices

- Team Resources

- Who We Are

- Notebooks:

- [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Berk2010-Daniela Daniela's Notebook]

- [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Berk2010-Christoph Christoph's Notebook]

- [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Berk2010-Amy Amy's Notebook]

- [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Berk2010-Tahoura Tahoura's Notebook]

- [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Berk2010-Conor Conor's Notebook]

Human Practices: Technical Biosafety Standards

Current Biosafety Standards

Biosafety is undoubtedly one of the highest priorities of any synthetic biology institution. Unforeseen consequences of genetic manipulation can be disastrous, especially when dealing with pathogenic organisms or virulence factors. The NIH and CDC have developed a standard of risk groups (RG) to rate the risk associated with different biological agents and genetic parts. They are summarized here:

- RG 1- Well characterized parts and organisms that are not consistently pathogenic to healthy adults.

- RG 2- Associated with mild human diseases, but do not readily spread through aerosols

- RG 3- Associated with deadly or severe human diseases that we have vaccines or treatments for.

- RG 4- Associated with deadly, aerosol-spread diseases that have no known vaccine or treatment

The existing framework primarily describes the scenario in which a specific gene or genes from one organism of known function is added to another reasonably-well characterized organism. The appropriate biosafety level is then determined by an intuitive analysis of the known properties of the source and destination organisms. When considering synthetic systems that involve many genes from many organisms, the task becomes more difficult. It is rarely the case the all the individual components used in a system were identified by the synthetic biologist, and it is also unlikely that the synthetic biologist is familiar with the full biology of the source organisms. Moreover, the assessment of risk is not as simple as when there are only two components. The question is then, how do we assess the risk of compositions of standard biological parts, and how can we document and communicate these risks to other researchers?

To a first approximation, the current NIH guidlines rate synthetic biological organism by choosing the highest risk group of all the parts within the organism and the risk group of the chassis. This risk can be upgraded if specific new risks are ascertained based on an intuitive analysis of the system. Additionally, a biosafety officer could lower the risk group if it seemed appropriate. This approach is essentially a two-tiered approach that involves a technical assessment of risk followed by a more subjective second-pass that involves a more nuanced treatment. The technical assessment is equivalent to describing the organism as having a list of devices with risk groups determined from their component parts. Though the risk can be downgraded by a biosafety officer, this simple analysis is the technical standard for deciphering the risk of genetically engineered organisms today. For example, our Vesicle-Buster parts this year contain virulence factor (RG2) coding sequences from the pathogen Clostridium perfringens, making the entire device RG2 (and thus ineligible for submission to the registry). So, in this instance, the risks associated with the device are triggered by the technical assessment alone prompting the synthetic biologist to consider more deeply what those risks might be. Furthermore, any organism created from those parts would be considered RG2 or heigher. Because of this risk, in consultation with our biosafety officer, it was decided that these materials should not be entered into the Registry. However, the materials and sequences will be made available to labs showing evidence of institutional biosafety authorization.

In addition, there is a list of "select agents" composed of specific organisms, specific proteins, and specific chemicals that carry the potential to be used as bioweapons. Since any organism composed of parts encoding proteins or biosynthesizing chemicals from the select agent list would contain the select agent, the resulting organisms would necessarily also be a select agent. In this case, their is no "second pass" to classifying the synthetic system as a select agent -- if it contains select agents it's a select agent. So, in effect, a similar logic to the technical assessment of risk associated with a synthetic composition can be used to implement both the select agent and risk group analyses.

Shortcomings of the System

As synthetic biology becomes more sophisticated and genes from various organisms are combined to make increasingly complex devices, unexpectedly dangerous constructs can be generated using seemingly innocent parts. During the design phase of our project, we discovered a combination of relatively innocuous parts that had the potential, in combination, to be hazardous.

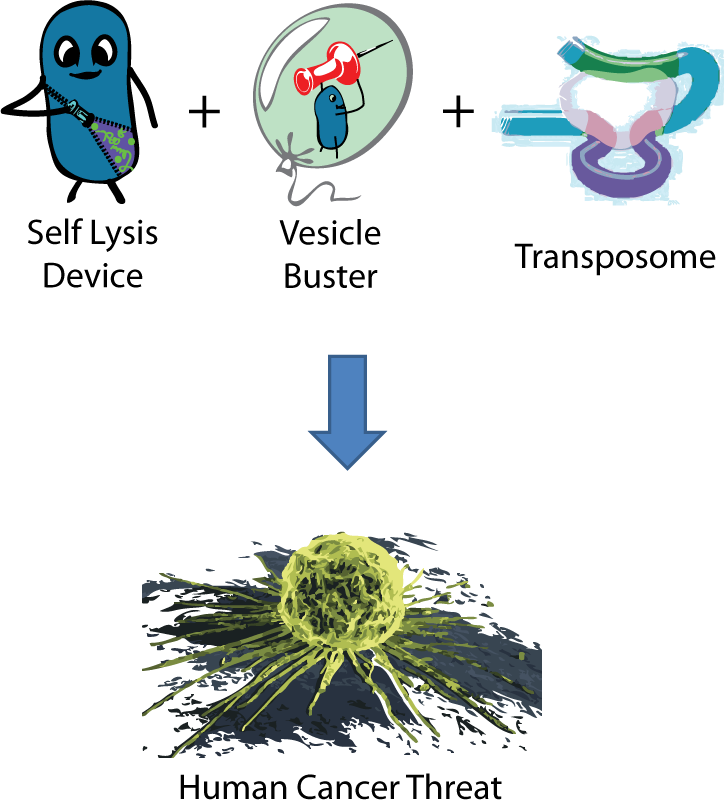

We created an engineered organism that used a Self Lysis device (made up of RG1 parts) to release its contents inside vesicles and a Vesicle Buster device (which contains RG2 parts) to break out of any cholesterol-based vesicle membrane. This device has been shown to function in mammalian cells. Lastly, we constructed a number of transposase devices (all RG1) to potentially integrate transposons into our target's DNA. We designed this combination of parts to deliver transposases and DNA to a lower metazoan in an attempt to genetically modify it. Alarmingly, if a bacteria containing this combination of parts entered the body and was exposed to a macrophage, it could quite possibly break into a human cell and deliver its payload, genetically modifying the human DNA. A transposon insertion in the wrong place in the DNA could be oncogenic. Fortunately, this risk was realized long before any parts were built this summer, and the necessary precautions were taken - our lysis device was put under inducible control to prevent undesired delivery, and all organisms that would combine transposon devices and payload delivery would employ strains deficient in iron acquisition. This well-established approach to attenuation reduces the risk of uncontrolled growth in biological fluids.

The discovery of this potential risk illuminated that the current biosafety rating system cannot identify potential threats from the combination of individually innocuous genetic parts. This is disconcerting, considering how the culture of synthetic biology is moving towards fast-paced construction and exchange of complex genetic parts. This could be dangerous to the scientists who are ignorant of the virulence they are synthesizing. The failure of government standards to recognize engineered threats also means that researchers could avoid regulations and restrictions that should reasonably required.

Working Towards A Solution

Future Ideas

Our Clotho biosafety monitor is only the first step towards developing new techniques for predicting the risk associated with engineered parts. There is still no effective method for predicting dangerous combinations of non-virulent genetic parts. The synthetic biology community must develop techniques to do this if it is going to be able to safely regulate biological innovation and gain the trust of the non-scientific public. However, developing computational tools to make such predictions will not be easy. A preliminary idea would be to develop function tags or classes for individual parts, based on BLAST results, and then scan for potentially dangerous composite functions for an entire part. For example, our Vesicle Buster would be tagged with a "membrane infiltration" tag (in addition to other tags) and one of our transposon parts would be tagged with "DNA manipulation". The program would recognize the combination of these two functions and it would be flagged since such a composite device could prove to be carcinogenic. Multiple tags would be associated with each part, such that our Self Lysis Device could be tagged with both "self lysis" and "protein release". This would expand the scope of possible composite functions. Clotho is designed to evolve with the synthetic biology community, and the determination of biosafety for composite parts is the next step in bringing synthetic biology to the level of regulation enjoyed by more entrenched engineering fields. Advances in computer models of biological and genetic systems bring the promise of deterministic predictions of complex enzymatic cellular effects, which would allow Clotho to not only define abstract risk groups, but to elucidate the potentially harmful biochemical mechanism in question and suggest possible countermeasures like the introduction of inducible promoters or other factors to control the potential risk of the proposed system. This is just an initial idea for a biosafety monitoring strategy, but ultimately whatever technical biosafety standards are decided upon, a uniform API will allow them to implemented in a uniform way. This foundation is what we have built with Clotho's biosafety feature. Developing this process further will require great collaboration, but improving our computational tools for predicting possibly virulent functions is a task that the synthetic biology community cannot afford to neglect.

"

"